I’ll admit it. The “how to” hermit crab shell of this piece sometimes feels a little silly. Like someone has bedazzled my shell and shoved me on stage with a white tipped cane. I mean, I—mere mortal—don’t actually know “how to be” right now! How am I supposed to write a how-to, even if it is a bit tongue in cheek? The levels of news tragedies and distractions in the world have reached peak chaos. Or have they? Is the real chaos yet to come? More than likely. Still, I tap my cane and dance on.

One thing I do know is that many people are having a hard time focusing right now. It’s no wonder with all that is going on: genocide, climate disasters, tech overlords sipping our time and money like college freshmen downing Goldschläger in 2008. Life is currently the Wild West of apocalyptic and energetic sinkholes. But here we are still trying to live life and move through it. In spite of it. And so, I continue to write this little hermit crab essay as an attempt to connect with other humans and share with everyone my writing and research resources.

If you missed it, here is Part I

PART II: How to Research Unknown Places (and Other Side Quests)

A) The Idyllic and the Alternative

Research is something you do best in a quiet corner of the library. Ideally with a stack of books gleaned from various sections. A few random books teeter on top of the large pile in your arms, books that just caught your attention as you passed by a shelf in a totally unrelated aisle. There is a comfortable chair and a roaring fireplace in a far corner of the library. Time, space, and comfort have joined hands like the United Colors of Benneton models in the 80’s. The research is going to flow.

What’s that spine say? Capitalism/Nature/Socialism? Don’t mind if you do add it to the stack.

This, of course, is a dreamy and rare research situation. As most of us are acutely aware this scenario is not usually possible. So how can writers find focus in an online world that is always pulling attention from the task at hand? In a space where technology has commodified our attention to such a degree we can no longer focus for more than a few seconds at a time?

Let’s turn to science for a moment. As Paul Atchley said in his study “Cognition in the Attention Economy” published in the journal Psychology of Learning and Motivation:

“Though our brain is adapted for simple environments, we live in an era in which we have access to more information and are surrounded by multiple distractions vying for our attention. This “attention economy” has redefined critical questions in cognitive science. The work of cognitive science must be translated to the current environment.”

When I first read Atchley’s imperative that we must bend to the current environment’s demands, it gave me pause. I live to resist! But then the more I thought about it, it made sense. “Adapt or die” spans the worlds of evolutionary biology, business, personally adapting to challenges, and even punk music. So when a cozy library day of research is not available and we have to research with the world’s noise clamoring for our attention, how can we simulate that space and simplicity—translate the feeling of a cozy library to our current environment? The key is to scratch our mental claws bit by bit into a state of focus.

Here is a list of ways to aid research focus I give students:

· Do Not Disturb mode is your friend. Whatever is on the other end of that text/call can probably wait for a couple hours.

· Limit all sound input for the first fifteen minutes until you find your mental focus. This may require noise-cancelling headphones.

· Hydrate! Make sure you have taken your vitamins and drunk plenty of water before sitting down to focus.

· Make a list of things you want to research. It’s okay to move beyond and deviate from the list, but just the act of making a list aids focus.

· Take it bit by bit. Start with an easy element off your research list. Pick one that doesn’t require a lot from you mentally. Once you check off that first part of the list you will gain confidence in your own tentative focus.

· Avoid Chat GPT. The whole point of researching is actually digesting the information and AI eliminates this crucial part of the equation.

· Tea. Somehow this became a running joke between me and some of my regular students from the Portland Community College Writing Center. I worked there for years (before, during, and after the pandemic) and had the privilege of working with people from all walks of life—refugees, nontraditional students, unhoused students, nursing students, academically gifted teens, students simply lacking direction, and more. The community college system is a beautiful, difficult hodgepodge. When we took the writing center to zoom during the pandemic it was quite a ride. Along with my fellow tutors, we became lone human touchstones for a reality gone haywire for students living in isolation. Dark times, you may recall.

But back to the tea. I always recommended tea to students because there can be a calming effect in the process of simply making a cup of tea and letting it cool down. Watching the way hot tea steams and evaporates can help mellow out the brain enough it might just catch focus. For me, it also helps regulate the nervous system. Not to overlook that tea is a delicious water delivering needed micronutrients to our bodies. During lockdown, a 50-year old male first-generation-to-college student in crisis who had never drank tea in his life did this, as well as making a research task list on paper. He later wrote me a letter of thanks for helping him not drop out of college. The tea works!

Lastly, I remind students that there can be real, simple joy in the process of research. It can be a gorgeous distraction from real life and the news cycle of doom. So when researching something that is unknown (a place, an ecosystem, space, whatever) it’s a way of extending known existence into new territory. As if the brain has go-go-gadget arms that reach and range into a new reality. How freeing! How nice to get away from the ever-closeness of existing in one’s own brain! Cheaper than airfare! Enjoy the ride and don’t spill that hot cup of tea.

B) Finding Parallels

Now that a tentative focus has been locked in, the mind is free to wander into the research du jour. When I was writing a novel that had a section set in Argentina in the early 1970’s, a place and time I’ve never been to, I took my own advice mentioned in PART I of this essay and wrote “adjacent to what I know.” In researching Argentina’s Patagonian region and exploring the ecosystem details, I was delighted to discover that there exists a similar natural system in the US that mirrors it from an entirely different continent.

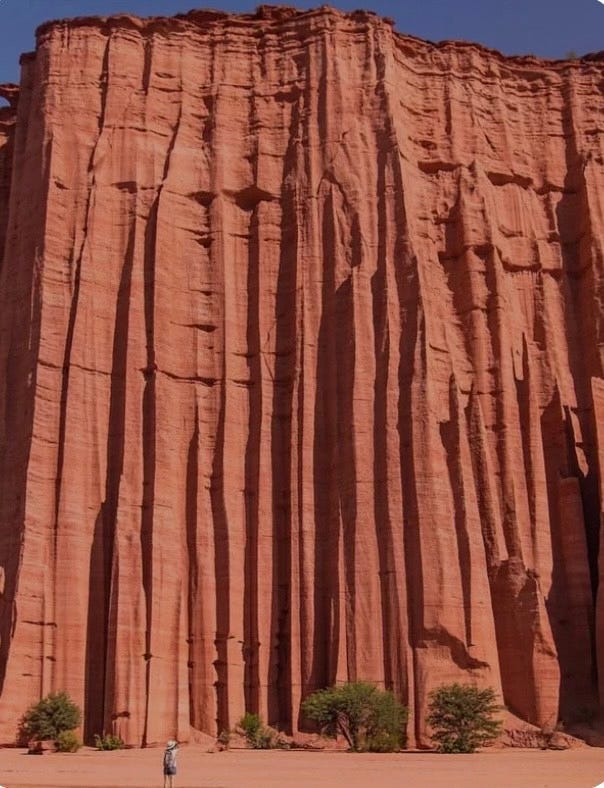

Argentina’s fertile central grassland pampas extend south and become Patagonia’s rugged steppe landscape. For the novel, I needed to get my brain to occupy the space where the two meet without actually going there (Yet! But I hope to one day). In the process, I was surprised to discover that in between these two ecosystems—in the ecotone—was a red dirt pillared desert much like the US desert southwest. So I dug into my own knowledge and experience working as a conservation field biologist in a more local ecosystem to understand how it might feel to be on the ground in what’s called the “Low Monte” of the Patagonian Steppe.

Talampaya National Park in Argentina. Photo credit: Creative Commons

The Burr Trail Road off Scenic Hwy 12 in Utah. Photo credit: Peggy Mekemson

In researching soils and fossil records in both places I noticed that the Patagonian steppe is built on ancient basaltic plateaus formed through extensive volcanic activity. The weathering of this basaltic bedrock contributed to the iron content and, consequently, the reddish color of the soil. Would that translate to the desert southwest where I had another novel character located? It couldn’t be that easy.

But it would, indeed, be pretty frickin’ smooth. The desert southwest has a similar history and is dotted with volcanic fields, basaltic volcanoes in particular. The associated landforms such as cinder cones and lava flows are sources of iron rich red soil. The two pictures above show how similar formations can occur thousands of miles apart.

After discovering the two mirror sources of red soil on completely opposite ends of the earth, I decided to see if the Low Monte also had ancient oceans as part of its fossil record. I was familiar with the ancient sedimentary layers in the Mojave desert from working on wildlife projects there. How deep into the earth’s crust would the similarities go?

They went deeper than I ever imagined. The Patagonian steppe not only also holds an ancient seabed, but similar fossil records, as well. The more I dug into one place and its geological, ecological, history, the more parallels emerged. Patagonia is famously a paleontology hotspot. Massive numbers of dinosaur fossils have been discovered there. Turns out so is Nevada. Both places supported sauropods and therapods as well as ichthyosaurs—marine reptiles that are technically not dinosaurs because they evolved from reptiles. Marine ichthyosaurs were enormous. Probably bigger than blue whales. And these creatures existed in both regions, roaming and eddying in the ancient oceans in tandem. Celestial beings weaving temporary magic from afar.

Interestingly, both regions also have large swaths of creosote plants that are drought resistant, an important feature in low rainfall areas. Creosote can withstand deep fluctuations in temperature, another feature of both places. These many and varied similarities work to show how similar environmental pressures can lead to convergent evolutionary adaptations in totally, geographically, distant desert ecosystems. Wild!

The process of discovering these similarities between the desert southwest and the Patagonian Low Monte felt like a revelation as it was happening over months and months of research. At time it felt like my brain had landed in miracle territory. Jesus on toast kind of stuff. But especially so because I had characters from my work in progress set in both places. I had entered into the research process without any expectations of finding this kind of symmetry. But I delighted in it. As each new detail emerged and mirrored, I felt like I had unlocked some minor secret of the universe. If you want to put it into a one sentence phrase please feel free to drop it below! I cannot quite simmer down the serendipity to a potent sentence droplet just yet.

But then, the differences emerged. And this started to feel just as important. The places, while so similar, created present day creatures of wildly different stripes. No one has ever rolled up on one of these in the desert southwest, as far as I’ve heard.

Meet the screaming hairy armadillo, a lil’ guy that thrives in the desert and arid grasslands of South America. Loves: burrowing and prosopsis pods. Hates: people who hunt his family for meat.

And mistakes, oddly enough, are what I think makes good fiction, as well. While in the research process I reflected on the way my two main novel characters, a mother and daughter, paralleled one another’s experiences and growth through trial and error. The daughter’s timeline was firmly planted in the desert southwest present day, the mother’s starting in Patagonia in the 1970’s then moving beyond to New York City and Cape Cod. Both characters make many, many mistakes And sometimes these women simply do not learn fast enough for the reader’s liking. All this to say, I could never have found my way through this particular, winding narrative form that now stands at a hefty, literary 400+ pages without their mistakes, small and large. The weaving and twisting of the two places and timelines would never have occurred if I had used AI for my research. The soul of the story emerged through the detours. It grew up through the cracks.

So maybe it’s really the differences that get at the heart of why existing as an individual matters?

It’s in the being and lightness of distinct patterns and shadows making their way across the globe.

We all fall under the shadow and shudder the same kind of sorrows.

Why knowing your own mind, and weaving your own path, indirect though it may be, matters. While the road (and this essay) is too full of commas, and parentheses, POV shifts, and maybe some filler prose here and there marking that you have strayed from the salient point, remember that it is ultimately the imperfections and the differences that make it all worthwhile. It’s what make you rooted in place. Make mistakes, writing and otherwise, and love them.

I began to imagine the plot and character connections of my imperfect Mom and daughter like a strand of DNA. Two distinct characters and timelines as a base pair connected by sugar phosphate backbone. It was very much an organic process that involved me (virtually) roaming the stacks and picking up random books along the way to add to my pile. It had to be imperfect and slow as I built the story. There was no easy or precise way through.

So I leave you with that. While on your next research journey, may you be inspired in some way to glean information the way a tree absorbs water—through a constantly growing system of roots smartly changing course as conditions ebb and flow. Like a creosote bush, may you adapt to the world’s harsh conditions around you and thrive. Wander the stacks and let yourself find focus and joy however you can. Just know that as you write and research, we are out here with you in tandem, us celestial ichthyosaurs, mirroring the journey and connected to you in ways unseen. There is beauty in our inexact unity. Humans can be analagous structures, too.

Hemispheres fold themselves into a red dirt grilled cheese?